The South Sea Bubble

2020 is a “Bubble Year.” Stocks, housing, and speculative ventures are all being inflated higher by the government’s printing press. 1720 was also a “Bubble Year” because of the English South Sea Bubble and the French Mississippi Bubble.[1] Understanding how the South Sea Bubble was inflated and popped by printing paper money is illustrative of current events. After all, those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.

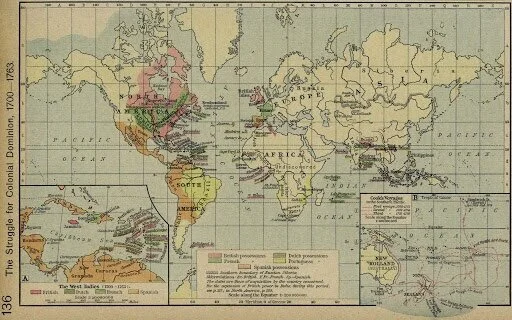

This story starts because Great Britain was in debt from years of war and bubble investments, particularly the Darien Scheme (1695-1700) and the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1713/1714).

Prior to 1707, Scotland and England were two different countries and Great Britain did not exist, even though both countries had the same monarchy since 1603 with James VI of Scotland (James I of England and Ireland). He commissioned the King James Bible.

Financially, Scotland was in even worse shape than England at the time. The Darien Scheme was Scotland’s own monopoly adventure in the South Sea with the African and Indian Company of Scotland in the colony of New Caledonia (Panama). It was supposed to be paradise; instead, people starved to death.[2]

In 1707, as a result of many Scottish nobles bankrupting themselves in the Darien Scheme and being bailed out by English taxpayers per article XV of the Act of Union, England and Scotland were unified as Great Britain under Queen Anne (1702-1714) and her husband, George of Denmark (1702-1708).[3]

However, the monarchy was still in debt. The debt was enormous, and worse, when the monarch died, the debt expired with them.

The problem of settling the monarch’s debt was being debated as more people were owed money. Just prior to King George’s death in October 1708, the issue of unsettled debt from his predecessor, King William of Orange (1689-1702), was discussed in the Parliament and addressed to Queen Anne.

According to the website British History Online,

“Six years after William's death the House of Lords took up the matter on its own initiative. On the 25th March 1708 it appointed a strong committee to draft an address to the Queen to pray her that the debts due to the officers and soldiers of the army during the life of William III should be stated and laid before the House of Lords ‘as likewise the debts owing to any persons, or such as represent them, upon the Civil List to the death of his late Majesty’ (Lords Journals XVIII, p. 552). The resulting draft address was adopted by the Lords four days later (29 March 1708) in the following form:

‘We your Majesty's most dutiful subjects, the Lords Spiritual and Temporal in Parliament assembled thinking it very just and reasonable that those persons who faithfully served the late King and their country in the war against France, as likewise those who served him in his household and family should be paid all that is justly due to them and the rather because several [soldiers] have obtained Acts for making out debentures in satisfaction of such debts, do humbly beseech that your Majesty will be pleased to appoint Commissioners to state all the debts that remain unsatisfied and are still due to the officers and soldiers and the arrears for service done in the late reign; and likewise to state what is still owing to any person upon the Civil List to the death of his late Majesty King William.’"[4]

So in 1711, after Queen Anne accumulated even more debt in the ongoing war over who would rule Spain, the South Sea Company was founded to help refinance her debt.

According to the investor Jesse Colombo,

“The South Sea Company was founded in 1711 by the Lord Treasurer Robert Harley and John Blunt, the former director of the Sword Blade Company. During this time, most of the Americas were being colonized and Europeans used the term ‘South Seas’ to refer to South America and other lands located in the surrounding waters. Robert Harley was responsible for creating a mechanism used to fund the British government’s debt that was being incurred during the ongoing War of Spanish Succession of 1701-1713”[5]

The mechanism created was that the South Sea Company would accept the monarch’s debt in exchange for shares in the company. Now people could use the mostly bankrupt monarch’s debt to invest in trade in the lucrative South Sea. Since the South Sea was mostly owned by Spain, having a friendly king on the throne was important.

According to Paul Cwik, a professor of economics and finance at the University of Mount Olive,

“Imagine a country that has been in and out of wars year after year. As a consequence, an enormous debt has accumulated and is difficult to pay off. (Stretches the imagination doesn’t it?) This was the situation that both England and France found themselves in the early 1700s. In England, some of the debt could be paid-off early, but not all of it and not without the permission of the creditor. Furthermore, this debt was between the King and the individual and could not be traded. In other words, if the King borrowed £1000 from you, he owed you. You could not sell that debt to another, and if the King died then the debt was cancelled. With all this debt hanging overhead, how does a King borrow more money to fight more wars? The solution came in three forms: the conversion of the King’s debt into the nation’s debt, the creation of paper money and with it the establishment of the Bank of England (as a central bank), and the chartering of a monopoly company.

The monopoly company was the South Sea Company. It offered equity shares in exchange for the previously untradeable debt. A creditor could exchange £1000 in government debt for shares in the company. These shares were tradable and the value would fluctuate on the open market. This allowed creditors to reduce their risk exposure to a government default or other inability to pay.”[6]

The Bank of England had been granted the power to print paper money that was backed by gold in 1694 (Exchequer bills),[7] and printed more money than they had gold so the monarchy wouldn’t go broke. If too many people tried to exchange their exchequer bills for gold, the bank could put redemptions on hold, as would happen from 1797-1821 after losing colonies in the American Revolution and fighting the Napoleonic Wars.[8]

By 1720, the share price of the company exploded higher. According to the website, Historic UK,

In 1720, in return for a loan of £7 million to finance the war against France, the House of Lords passed the South Sea Bill, which allowed the South Sea Company a monopoly in trade with South America.

The company underwrote the English National Debt, which stood at £30 million, on a promise of 5% interest from the Government.

Shares immediately rose to 10 times their value, speculation ran wild and all sorts of companies, some lunatic, some fraudulent or just optimistic were launched.

For example; one company floated was to buy the Irish Bogs, another to manufacture a gun to fire square cannon balls and the most ludicrous of all ‘For carrying-on an undertaking of great advantage but no-one to know what it is!!’ Unbelievably £2000 was invested in this one![9]

In January 1720, the British South Sea Company’s stock price was £128. By June the price was £1,050. The economist Douglass French writes in his book, Early Speculative Bubbles and Increases in the Supply of Money,

“By the late spring, early summer of 1720, foreign buying began to push the price of South Sea stock ever higher, as investors fled Paris in ever increasing numbers. Also, specie from Holland began to arrive in London to be used for the purchase of shares. At the same time, the Company gave Exchange Alley a liquidity injection by giving the directors the power to lend money on the security of South Sea stock. This action produced £11 million in loans. At the same time, the Bank of England was throwing gasoline on the fire in the form of loans on its own stock. The government also got into the act by lending the South Sea Company £1 million in Exchequer bills that were subsequently used to purchase the Company’s shares.”[10]

By September 1720, the price has plunged back down to £175 per share.

According to the Harvard Business School,

“The Bubble Act was passed in June, requiring all joint-stock companies to receive a royal charter. The legislation had been introduced by the South Sea Company, presumably as a means of controlling competition in the burgeoning market. The South Sea Company received its charter, perceived as a vote of confidence in the company, and by the end of June its share price had spiked to a peak of £1050.

Investor confidence began to wane, however. The sell-off began by early July and the collapse occurred quickly. By the end of August stock was valued at less than £800. By September the share price had plummeted to £175, devastating institutions and individuals alike. In 1721 formal investigations exposed a web of deceit, corruption, and bribery that led to the prosecution of many of the major players in the crisis, including both company and government officials.”[11]

As with the Scot’s misadventure in the South Sea with the Darien Scheme, the South Sea Company was simply fraud. The French Mississippi Bubble would also burst in 1720 for the same reason. Speculators thought that someone would buy their shares at a higher price, because stocks always go up when the government prints money to buy stocks.[12]

David Portnoy of Barstool Sports, live-streaming his day-trading (August 2020).

The South Sea Scheme was even mentioned in Cato’s Letters, pseudonymous essays published by John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon in the London Journal from 1720-1723. The letters would inspire the American Revolution, the Federalist Papers, and the Anti-Federalist Papers.[12][13]

In the second letter, The Fatal Effects Of The South-Sea Scheme, And The Necessity Of Punishing The Directors, published on November 12, 1720, Cato wrote,

“As never nation was more abused than ours has been of late by the dirty race of money-changers; so never nation could with a better grace, with more justice, or greater security, take its full vengeance, than ours can, upon its detested foes. Sometimes the greatness and popularity of the offenders make strict justice unadvisable, because unsafe; but here it is not so, you may, at present, load every gallows in England with directors and stock-jobbers, without the assistance of a sheriff’s guard, or so much as a sigh from an old woman, though accustom’d perhaps to shed tears at the untimely demise of a common felon or murderer. A thousand stock-jobbers, well trussed up, besides the diverting sight, would be a cheap sacrifice to the Manes of trade.”[14]

Today, stocks are also being inflated higher with government debt. The Federal Reserve, the central bank of the USA, prints money, buy’s government debt from banks, and the banks have new money with which to invest while the government can hand out stimulus cheques.[15][16]

The Chairman of the Federal Reserve even announced that they would keep printing money to support the flow of credit as recently as September 16. Per the FOMC’s official statement,

“In addition, over coming months the Federal Reserve will increase its holdings of Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities at least at the current pace to sustain smooth market functioning and help foster accommodative financial conditions, thereby supporting the flow of credit to households and businesses.”[17]

The lesson is that gambling into the stocks of bankrupt countries that are printing money works until enough people want to cash out.

Like when playing poker, only the people who cash out make money. Like poker players in a busted casino, even prudent gamblers can’t cash out their chips if the casino has no money.

Today, the chips (dollars) aren’t even redeemable for money (gold), while the chip makers still own gold.

For example, Doctor Ron Paul, while a Congressman representing Texas, was the Chairman of the House Subcommittee on Monetary Policy and asked Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke about gold during a hearing in 2011.[18]

Paul: Do you think gold is gold money?

Bernanke: No

Paul: Even if it has been money for 6,000 years, somebody reversed that and eliminated that economic law?

Bernanke: Well, it’s an asset. Would you say treasury bills are money? I don’t think they’re money either but they’re a financial asset.

Paul: Why do central banks hold it?

Bernanke: Well its a form of reserves

Paul: Why don’t they hold diamonds?

Bernanke: Well its tradition. Long term tradition.

Paul: [Laughing] Some people still think it’s money. I yield back. My time is up.

The casino already cashed out.

Hindsight is 2020.

[1]https://www.hamiltonmobley.com/blog/phseyvr2uymtcom264fgfsyrqcydhk

[2]https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/may2005.html

[3]https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/heritage/articlesofunion.pdf XV “In the next place, that the capital Stock, or Fund of the African and Indian Company of Scotland, advanced together with the Interest for the said capital Stock, after the Rate of 5 per Cent. per Annum, from the respective Times of the Payment thereof, shall be paid; upon Payment of which capital Stock and Interest, it is agreed, The said Company be dissolved and cease.”

[4]https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-treasury-books/vol17/pp941-946#p1

[5]http://www.thebubblebubble.com/south-sea-bubble/

[6]https://mises.org/wire/south-sea-bubble

[7]https://www.british-history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol6/pp483-495 Clauses XXV and XXVIII

[9]https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/South-Sea-Bubble/

[10]https://cdn.mises.org/Early%20Speculative%20Bubbles%20and%20Increases%20in%20the%20Supply%20of%20Money_2.pdf The South Sea Bubble, pg 99.

[11]https://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/ssb/history.html

[12]https://mises.org/library/catos-letters-liberty-and-property

[13]https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/art/artifact/Sculpture_22_00004.htm

[14]http://oll-resources.s3.amazonaws.com/titles/1237/Trenchard_0226-01_EBk_v6.0.pdf Page 29

[15]https://www.hamiltonmobley.com/blog/ch4l2ssqmdngldxo3xegkol02ngiqu

[16] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/fedfunds “The effective federal funds rate is essentially determined by the market but is influenced by the Federal Reserve through open market operations to reach the federal funds rate target. […] Similarly, the Federal Reserve can increase liquidity by buying government bonds, decreasing the federal funds rate because banks have excess liquidity for trade.”

[17]https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/monetary20200916a1.pdf